How Bernd Gaiser Founded the First Berlin Pride in 1979

Gay pride instead of shame

When Bernd Gaiser moved to West Berlin in 1967, in his early twenties and head over heels for a man, neither SchwuZ nor Berlin Pride (in German called CSD, short for Christopher Street Day) existed. The places gay men frequented were barred with thick doors, where those wishing to enter endured critical looks thrown through narrow slits. Paragraph 175, which criminalized consensual sex between men, was still binding in the strengthened Nazi version. The Federal Constitution Court had even upheld the law in 1957. But all of that was to change soon, and Bernd Gaiser is one of the protagonists of this transformation. He was born in 1945 as a small-town boy in Nussloch, Baden-Württemberg, in the south of Germany. He grew up in Edingen-Neckarhausen, learned the job of publishing assistant and completed his basic military training. While at the Marines, he was brutally confronted with the precarious situation of gay existence in illegality. A friend committed suicide after being discharged from the army and threatened with a lawsuit under §175.

Bernd Gaiser decided to counter the private shame and state discrimination with a sense of gay self-esteem. As soon as he arrived in Berlin, he dove into the nightlife, the political circles around universities and the building of structures that allowed people to be as gay as they wished. In 1969, he founded a shared living community with his friend Ulrich Baer. That same year, §175 was softened and sex between men over 21 was legalized.

Someone said: „You should have been gassed!”

In the following ten years, Bernd Gaiser was everywhere where gay self-esteem stirred and organized: he debated and built. Out of nowhere, this time brought an infrastructure of places, groups, publishing houses, and newspapers. “We had nobody to look up to,” Gaiser later said in interviews. In 1971, Rosa von Praunheim’s “Nicht der Homosexuelle ist pervers, sondern die Situation in der er lebt“ (not the homosexual is perverse, but the situation he lives in) was shown in Arsenal cinema in Berlin-Tiergarten, and Bernd was there to watch. The audience took the film’s slogan “Raus aus den Klappen, rein in die Straße“ (out of the gloryholes, onto the streets) seriously and passed around a contact list to found the Homosexual Action West Berlin (HAW). Bernd wrote down his name and has shaped the HAW ever since. (the Schwules Museum is showing an exhibition by photographer Rüdiger Trautsch on the topic in the summer of 2023.)

The gays of HAW were different from the discreet barflies of Nollendorfplatz behind their thick doors: they were loud, they had long hair and bears, and they read Marx and later Foucault. Most of all, they didn’t want to hide anymore. Spontaneously, they would run into the bars of the subculture, sit down on the floor, call “Gays, out to the streets!”, and drum a rhythm on the floor. During the day, Gaiser worked as a clerk in the successful Keipert bookstore in West Berlin, where the students of the 68 movement also shopped. The rest of his time was spent loving, fucking, fighting, debating, writing, and dancing in the movement. Especially sex was omnipresent during the 70ties. Greedy for life, hungry for love and with the revolution in their minds and hearts: Gaiser and his comrades talked till their throats went dry, kissed till their lips were sore and danced till blisters covered their feet.

But despite how fast the movement was going; social development was dragging its feet. At the first gay demonstration in West Berlin in 1973, someone hissed at Gaiser: “You should have been gassed.” With growing structures came the first conflicts: When French and Italian “Tunten” – a German term denoting effeminate gay men, often used as a slur but reclaimed by some – came to a demonstration following the first European Gay and Lesbian Gathering in dresses and drag, the famous “Tunten-fight” broke out.

1979: the very first Berlin Pride

Some gay men from the movement criticized the Tunten: that they were chasing away the shy doe of the proletariat with their effeminate clothing and so were hindering the revolution. Gaiser and the “feminist” fraction he belonged to, however, believed strongly that playing with gender and effeminacy is a necessary part of queer emancipation. This notion was described by Ronald M. Schernikau seven years later in his small-town novel “am female. am male. am double.”

Following this, the feminist fraction separated themselves from the main group. From this fraction arose the gay center that would become SchwuZ (an abbreviation for the German Schwules Zentrum). Bernd Gaiser, of course, was part of the process. In SchwuZ, the first Tuntenensemble of West Berlin performed: Mechthild von Sperrmüll, Pepsi Boston and Melitta Sundström, among others, glittered and giggled through the fourth floor of Kulmerstraße 20a.

Committed to literature since his youth, Gaiser brought gay writers together for a three-day conference in 1978. During this time the publishing house Rosa Winkel was born, co-founded by Gaiser’s flat mate Egmont Fassbinder. One year later, he published “Milchsilber. Wörter und Bilder von Schwulen“ (Milksilver. Words and books of gay men). Shortly afterwards, Gaiser‘s friend Andreas Pareik returned from a trip to the US and over the nightly beer in SchwuZ told stories of the preparations for the tenth anniversary of the Stonewall Riots. From these beers, the plan arose to celebrate this anniversary in Germany as well, with a demonstration not only of gay men but all people in the movement.

„what’s left is what’s left of life.”

Quickly, the versed activists rallied their friends, printed leaflets and spread them in bars, hit up everyone down to long-lost lovers and solitary SchwuZ drinkers, and marveled at the 500 people on the streets on June 30th, ready to celebrate the first Berlin Pride. “Make your gayness public!” and “Lesbians, stand up and the world will see you!” were the slogans of the moment. That day, Bernd Gaiser saw what in other places already carried the name queer: that there is more to the movement than gay men.

The societal atmosphere was different now than five years before: passersby on the Ku’damm smiled at the queers on the street – the result of the movement’s efforts. Bernd Gaiser worked as a journalist for several gay newspapers and founded the Maldorer Flyers in 1981.

One year later, the first documented German case of AIDS. Surrounding Bernd Gaiser, friends and lovers fell ill, many died. Caring for their HIV-positive loved ones and mourning was the call of the hour. Joining that was the anger at the societal ignorance and those politically co-responsible for the epidemic, who fought the sick and not the sickness. Jürgen Baldiga, himself succumbing to his severe AIDS in 1993, interviewed and published by Gaiser, wrote about this time:

“j. is dead

is dead

is dead

is dead

and so on

what’s left

is what’s left of life.

live faster,

live more intense.”

“Gays invent happiness.“

Bernd Gaiser survived and turned a new page: gay aging. He visited lonely community elders in the 90ties and established the Elders group of Berlin Pride. From 2005 to 2021 he helped develop the Living Space Diversity in Niebuhrstraße and created the first queer multigenerational home. He himself moved in in 2012, saying goodbye to the shared flat he had lived in since 1977 with Egmont Fassbinder and Wolfgang Theis, cofounder of Schwules Museum.

In 2017, he published his texts with Maldorer Flyers. In 2017 he was awarded the Soul of Stonewall Award by Berlin Pride, by then grown into a mass happening. Until today he continues to write about literature online. Throughout his life, he proved the title of his blog again and again: Gays invent happiness.

Further information

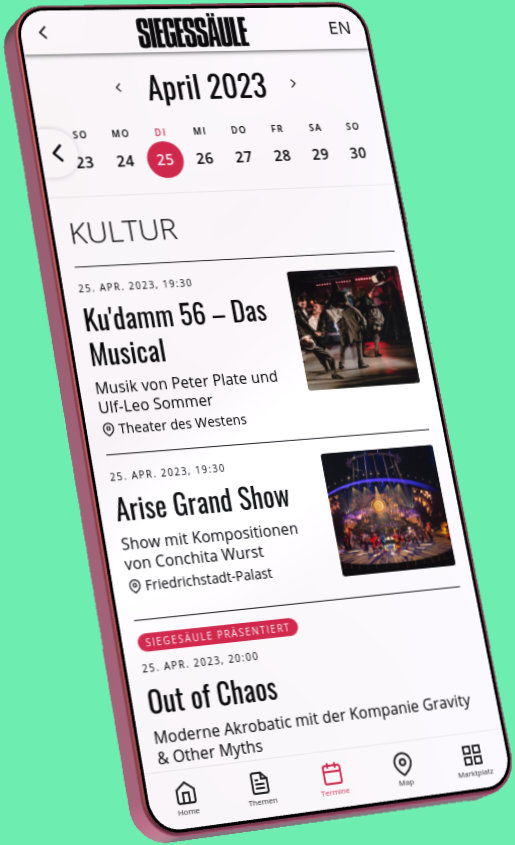

44 years later and proud: All dates for CSD Berlin und Prides 2023

Subscribe to Place2be.Berlin's Instagram channel for the latest info and impressions from Berlin!

The Place2be.Berlin city map shows you interesting queer locations all over Berlin.

You can find a complete overview of all events for every single da on the event pages of SIEGESSÄULE, Berlin's famous queer city magazine.

Words: Mowa Techen

Translation: Jara Nassar